Part Seven: What Makes Sci-Fi Great

“Individual science-fiction stories may seem as trivial as ever to the blinder critics and philosophers of today--but the core of science fiction, its essence . . . has become crucial to our salvation if we are to be saved at all.” -Isaac Asimov

“I don't think Homo sapiens possesses any divine right to the top rung. If something is better than we are, then let it take the top rung. As a matter of fact, my feeling is that we are doing such a miserable job in preserving the Earth and its life forms that I can't help but feel the sooner we're replaced the better for all other forms of life.” -Isaac Asimov

There’s a conceit among many famous Science Fiction authors. In fact, it’s so endemic I would go so far as to say that this is one of the core struggles of Sci-Fi in general. You’ll scarcely find a popular Sci-Fi story without this unresolved tension because most of the landmark authors never resolved it in themselves. At one moment, they can rise to the most profound and salvific imagery, and in the next, descend into absolutely mind-shudderingly banality. I wouldn’t even go so far as to call it nihilism because nihilism still hints at a romantic struggle against an indifferent universe—at least before it got subsumed by Neil Degrasse Tyson wannabes. Sci-Fi can be (and often is) both stirring to the soul and utterly mundane, both an inspiring call to action and a slothful shrug at inevitability. So often, it’s both beautiful and horrendously depressing.

And what is so perplexing about this genre is how both these aspects sit practically side-by-side in so many of the lauded stories we hold up as the great works of art. We’ve all read or watched that one story that took a sudden, unpleasant detour. The ones coming to my mind right now are Larry Niven’s diatribe about population control in Ringworld, Isaac Asimov’s extensive subplot about three-way alien intercourse in The Gods Themselves, and even from an author I otherwise like, Edgar Rice Burroughs—he had some choice words about the dangers of religion in The Gods of Mars.

I’ve spoken about this contradiction before in an earlier essay, but I believe there’s a misunderstanding about what Sci-Fi actually is that is partly to blame for this contradiction. If you were to ask any of the popular names what the purpose/nature of Sci-Fi is, they would give you a few of these answers:

“Science fiction is the most important literature in the history of the world, because it's the history of ideas, the history of our civilization birthing itself. ...Science fiction is central to everything we've ever done, and people who make fun of science fiction writers don't know what they're talking about.” - Ray Bradbury

“One of the biggest roles of science fiction is to prepare people to accept the future without pain and to encourage a flexibility of mind. Politicians should read science fiction, not westerns and detective stories. Two-thirds of 2001 is realistic -- hardware and technology -- to establish background for the metaphysical, philosophical, and religious meanings later.” - Arthur C. Clarke

“Science fiction isn’t just thinking about the world out there. It’s also thinking about how that world might be—a particularly important exercise for those who are oppressed, because if they’re going to change the world we live in, they—and all of us—have to be able to think about a world that works differently.” - Samuel R. Delany

“Science fiction is held in low regard as a branch of literature, and perhaps it deserves this critical contempt. But if we view it as a kind of sociology of the future, rather than as literature, science fiction has immense value as a mind-stretching force for the creation of the habit of anticipation. Our children should be studying Arthur C. Clarke, William Tenn, Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury and Robert Sheckley, not because these writers can tell them about rocket ships and time machines but, more important, because they can lead young minds through an imaginative exploration of the jungle of political, social, psychological, and ethical issues that will confront these children as adults.” - Alvin Toffler

“Science fiction is not prescriptive; it is descriptive.” – Ursula K. Le Guin

If you skipped all those quotes, I don’t blame you. Here’s the short version: the overwhelming consensus is that Sci-Fi (insofar as it is striving to be high art) is a sociological genre meant to explore technological/philosophical concepts. It’s about predicting and exploring problems of the future in an entertainment medium and about tackling serious issues that might come up in the near present or future of humanity.

Here’s the thing. I disagree entirely.

Generally speaking, I don’t think the vast majority of Science Fiction has anything particularly unique to say on the future. And from a philosophical/technological standpoint, even the most prophetic of the classic works of sci-fi literature could be better described as fever dreams rather than serious dissertations on our sci-fi future. Just look at most of the great classics, and you’ll quickly see how hilariously this illusion falls apart. Remember all those far-flung sci-fi stories that were set in the distant future of the 2000s and 2010s? We were supposed to be colonizing the solar system decades ago! If they can’t get the basic timelines right, why should anything else be taken seriously? It turned out to be a farce to think we would have the world of Blade Runner by 2019. So why isn’t the whole thing a farce? Why do we so easily believe in such a world so long as its another few decades away? Why do people take seriously the possibility of androids when we couldn’t even get flying cars to work?

And since we’re on this, “Sci-Fi is descriptive” tangent, of all the classic Sci-Fi works, how many had mass immigration, global fertility collapse, and racial/religious tensions as the prevailing crises in the West’s imminent future? How many stories presented the utter collapse of rationalism and atheism? Star Trek didn’t see that one coming, that’s for sure. Most stories of the far-future thought some form of rationalism was going to be the default. But the way things are looking, it’s not going to last another hundred years, let alone the next thousand. Dune may have called it, but Dune also stands alone.

How many talked about the discrediting of every mainstream scientific and political organization? How many about the horrors of social media, the dating crisis, the impoverishment of American and European peoples?

And how many of those authors talked about those things accurately? It’s one thing to predict robots will replace human labor. Yeah, yeah, everyone could see automation looming on the horizon. But how many of those stories were focused on robots replacing factory workers and manual laborers? Something that is still in its earliest infancy? How many of them talked about the issues we actually face in 2025? With braindead chatbots and AI image slop?

I’m not worried about Skynet nuking the Earth. I’m worried whether my surgeon used ChatGPT to cheat on his exams. And let’s go a little further. How many Sci-Fi stories were talking about the dangers of bionic racism? Offhand, I know multiple franchises that all focused on this singular issue. And how many didn’t say one word on grooming gangs, subway shootings, and erm… certain FBI demographic statistics?

All right, so we’ve narrowed it down to the Cyberpunk and Post-Apocalyptic authors who were providing the real social commentary. But less of the cyber and a lot more of the punk. We’re aren’t living in the netrunner future so much as Children of Men. Except a lot more politically incorrect than Children of Men, if I recall correctly.

So the real books of sociological value were less Neuromancer and more 1984, Brave New World, and Abolition of Man? If we’re going by the standard Sci-Fi authors set for themselves, most are utterly BTFO’d on arrival. Forget Hyperion, it’s books like The Camp of the Saints that provided any real insight into the future, something I suspect most of the authors I quoted would be very uncomfortable about. How many of them were forewarning stuck culture, the re-establishment of racial castes, and the incompetency crisis? We had thousands of stories about pandemics and overreach of the pharmaceutical industry, but how many of those narratives foresaw the Tiktok dance videos and the George Floyd riots? Even the most dystopian and totalitarian visions of the future very rarely took into account the effeminacy, the banality, the day-to-day.

What does that say about the vast majority of Sci-Fi stories? What does that say about the genre as a sociological tool? Far from being a guiding star for humanity, only a fraction of it ever had anything really relevant to say about our current technological and sociological predicaments. At best, they were like half-envisioned anxieties filtered through a mirror darkly. The prescient Sci-Fi story was always diamond in the rough. The one that provides a roadmap for the next ten years is non-existent—let alone the vast timescales that are so part and parcel of the genre.

And if we’re really still bent on Sci-Fi as a sociological tool, I would also like to question our map makers. Look into the lives of many sci-fi authors and the ideologies they promoted. You’ll quickly find the genre is populated by the very types of people who sent the West careening off a spiritual and self-existential cliff. If Sci-Fi could not and did not prevent 2020, the very dystopia everyone was screeching about, then of what use is science fiction? This purported tool of averting the worst of scenarios failed catastrophically, and the only reason we have any hope is because a bullet missed by three inches on the very man most of these authors would have denounced!

The point is, Sci-Fi stories are not about mass propagandizing the public (at least, that’s an abuse). They’re not about the future. They’re not about the application of technologies or examining potential sociological issues. Nothing about Sci-Fi is about trying to chart a course into the unknown. Any look at a Sci-Fi story from just a few decades ago tells us far more about what it was like back then instead of now. Forget the future, these stories only really tell us what fantasy storytellers thought at the time.

And that’s just what every Sci-Fi story ever written is—a fantasy.

It’s magic. It’s all magic. And that might be something very easy to spot with something like Star Trek, but it honestly applies to all of storytelling. It’s all a glamor. Even with something more contemporary like True Detective or Breaking Bad where the rules of the world more or less line up with our own. Because even if those rules appear to be our own, they are fundamentally not. The only rules fiction obey are the writers’ rules. And it is only the suspension of disbelief that convinces us otherwise.

It’s all fantasy. It’s all shadows on the wall. And these shadows have so much power that they have intellectual elites talking about the pros and cons of AGI and Mars colonization—regardless of how feasible those things may or may not be. A lot of people treat Martian colonization as a reality to be considered, a discourse to be had, when the jury’s still out on basic things like how badly the human body might deteriorate under low gravity. There’s a million things that barely touch the mainstream discourse, like Mars’ high surface radiation, to the catastrophic failures of creating closed ecosystems, to basic things like reproductive health. There’s so much that’s up in the air, and yet people treat Mars colonization as real. They can flip on a tv series where the peoples of Mars are launching an interplanetary war with Earth, and they’ll take it seriously. When in practice, it might be no less ridiculous than Frodo riding up to Mount Doom in a Honda Civic.

People would burst out laughing if the BMW scene actually happened in the movies, and yet, they’ll take seriously things ten times more preposterous like faster than light travel, aliens blowing up famous monuments, and yes, also the N.C.C. 1701 Enterprise.

The Enterprise is practically and functionally indistinguishable from magic. And all of this is to say that Sci-Fi itself is practically and functionally indistinguishable from fantasy. It does not matter how hard you do your research or how accurate your spaceships are to what we think they might look like. Just by the nature of storytelling itself, it’s all magic. The only crucial difference between Sci-Fi and Fantasy is aesthetic, and that’s why Sci-Fi is so important.

Sci-Fi is the only fantasy genre people still believe in.

When you turn on a movie and watch Lord of the Rings, you get transported to another world. But it’s not your world. True to Tolkien’s escapism, you are only visiting, breaking out of the prison for a little while. But besides the Shire, it’s not an active dream for people to work for. We can’t bring Lord of the Rings into visceral reality, and no one comes away thinking elves or dwarves will be having an impact on their life.

Star Trek is magic, but it’s a magic people believe in. Space exploration (and especially FTL), is no different than discussing elves or dwarves in 90% of lay discourse. Practically no one talks about mechanics, no one outside the nerds is getting down to the nitty gritty. But these concepts float around anyway. They captivate the imagination. They’re the modern folklore.

Sci-Fi is the magic that could be real. Stories didn’t change with modernity, only the tropes and forms.

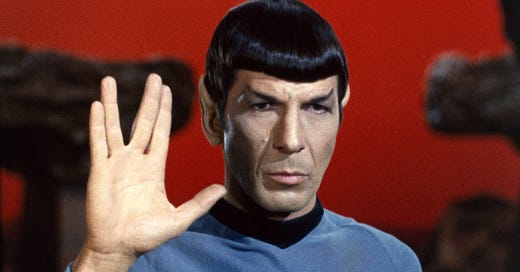

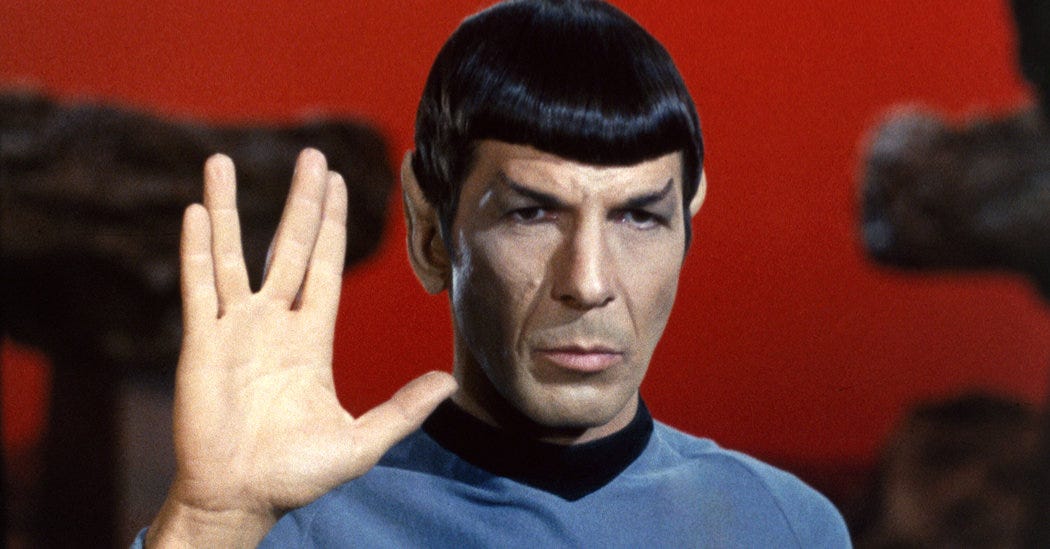

What so many Sci-Fi authors fail to see is that the beating heart of Sci-Fi is not the ideology or the sociology or even the particular ideas. It’s not about the political lens or outlining your 500 page manifesto. Sci-Fi is no different than any other fiction genre. It’s about trying to reach at the real, the numinous. What made Star Trek great was not the rationalism or the ideas of the far future. What made it great were the same things as in any other well told story.

It’s about life. It’s about those things which we experience every single day in our lives, but presented in a way that reminds us that the world is mysterious and dangerous and hopeful and tragic. It’s stepping out of the mundanity of our lives and reminding us that existence itself is a miracle.

What made Star Trek great were all those times it stepped down from the soapbox and simply became heartfelt. It’s about the frontier of the unknown, a world where there are adventures still to be had. Foreign lands and peoples, where every corner is new. It’s about traveling and exploring and sometimes conquering. It’s about setting off on a tiny ship towards the horizon, where there be monsters and demons and muttering cannibals, ancient temples to chittering computers and hidden technology. It’s about mad androids and strange, crystalline entities. It’s about stepping on a world where everything is upside down and the people are all clones.

It’s about comrades in arms. It’s about a crew, sometimes a family. It’s about love and rage and death, the burden of command, authority, impulsivity. The desire to go out and climb the tallest mountain because it’s there. It’s about the good times and the bad. It’s about the reckless, the braggadocious, the daring. It’s about staring into the face of death and having the reaper blink first. It’s about outwitting, outracing, outfighting everyone who thought you would fail. Flying higher and farther than anyone has gone before. It’s about plunging into the depths of hell and walking out on the other side.

It’s about war and peace, about a struggle with your brother to the death. About good and evil men. It’s about the man who rises to the hour and the villain who brings fire upon a whole world. Those who persevere and the cowards. It’s about finding God. It’s about the prophets and the thieves, the man who cannot tell a lie and the man who can’t stop lying. It’s about the sweet taste of an impossible victory and the despair of a crushing defeat. It’s about courage and honor and strength.

It’s about friendship, brotherhood.

Tragedy.

Look to the moments that stir the soul. It’s never the dry philosophizing. It’s the men.

Part Eight: The Best of All Worlds

In the first installment of this essay, I discussed the six captains and the spiritual mode of each of the Star Trek series. But now I would like to take a closer look at some of the characters and subplots of this long-running franchise. There’s so much content to write about and so much to discuss, and this essay series is already a novella. So to keep this concise, I’m just going to go ahead and pick my five top things from each show and talk about them.

For my patient and wonderful paid subscribers, I’m going to open up the opportunity for requests that I will make into the fourth installment. If there’s anything you want to see me talk about, please reach out. This can be anything from certain characters to episodes to plot arcs and movies. Nothing is off the table. And I’ll end this essay series on a final reflection of some of the good memories this franchise made, not just for me, but for you all as well.

I know I’m cheating with a movie, but really, can you blame me? This is a dissident review, and Khan Noonien Singh is a great man of history—and one of the only times Star Trek really sold you on it. Now before I get someone thinking I’m saying he’s a good person, no, not at all. A great man of history is simply a person who unquestionably leaves their mark on the passing of events—for good or ill. Ghengis Khan, the real life counterpart to our sci-fi conqueror, is a great man of history. What I’m simply describing is that ineffable quality that raises men into world leaders, theologians, scientists, and yes, also conquerors.

I’ve spoken earlier on how in order to create conflict—in order to create good stories—writers had to abandon the utopian aspects of Star Trek. And the more they strayed from those parts of Star Trek that were a political manifesto, the better the story got. And when it fully thrust itself into the mode of human drama, we finally got the brilliant movie Star Trek II: Wrath of Khan.

Khan was the closest Star Trek got to Shakespeare. Even in his original appearance in the episode Space Seed, there was a sense of foreboding about the man, a premonition of what was to come. He was a larger than life character, both in-setting and out. A genetically crafted superhuman with a genius intellect and a ravenous ambition.

That’s the thing that makes Khan so different than all the villains who came before and after.

He’s a man of ambition.

Khan is the most illiberal character in the entirety of Star Trek. He doesn’t apologize for it. It’s not sugarcoated or otherwise danced around. He’s not castrated by the script or comically exaggerated by writers uncomfortable with the material. Unlike so many other times in Star Trek, the character is given room to breathe and thus the tragedy is allowed to unfold.

It’s an easy thing as a dissident to be contrarians and argue that Rightwing villains in Leftwing media are right, but there is a much deeper discussion to be had with Khan. Because the characters themselves are symbols. And what the Left love to do is to pervert these representations into caricatures that are incongruous with the archetypes and truths we experience in the real world. But Khan was a character that was allowed to be expressed honestly.

He’s a walking, talking Rightwing idea because he represents those forces which the utopian Federation denies. He’s the type of man Star Trek claims to have eradicated in the far future. And in just existing honestly, he’s a contradiction to everything the Leftist side of Star Trek stands for.

After all, even if Star Trek denies this, we know in real life that there will always be more men like Khan.

Data represents another contradiction that runs to the very heart of what Star Trek represents. I would say his character archetype technically begins with Spock and then we see several iterations of the same theme over the course of the whole franchise, especially in Voyager with the Doctor and Seven of Nine. Star Trek loves to take that which is decidedly inhuman and progressing them to a real humanity. The logical and cold-hearted Spock forms a brotherhood with Captain Kirk and McCoy. Data is a retelling of Pinocchio in the future. Both the Doctor and Seven of Nine learn to understand themselves as individuals. And I suppose T’Pol from Star Trek: Enterprise has her own arc with chemically induced brain damage.

Some of you may expect that I will cry foul here. After all, there’s an easy criticism to say this is another part of the Progressive tendency to extend empathy to the other. The Left stories of extending empathy to the out-group, and Data is just another manifestation of this inclination. However, I believe there is a more subtle beat here. One that is older and far more nuanced than Progressive identity politics.

Are we ourselves not on the same path Data and all the rest are? While we are indisputably human in the sense that it is our species. Are we fully human in what we ought to be as humans? And are there not parts of ourselves that are just as lacking—or dare I say artificial—as Data? I’m sure we’ve all met that shallow person in our lives who lives without a trace of sincerity. Are there not parts of ourselves that aren’t sufficiently grown in virtue, that come off hollow? I think any man of introspection would say yes.

The juxtaposition of the artificial versus the real is a clever literary device, highlighting aspects of the human soul that would be difficult to draw out otherwise. And the artificial thing becoming human certainly has a valid storytelling tradition, if only because we ourselves begin as artificial substances.

But there is another contrast, one unintentional by the writers, that Data delightfully hints at. After all, if Data’s story is all about becoming human, isn’t the Enterprise’s story becoming less human? Surely we represent a dwindling demographic as the Federation expands into the galaxy, incorporating hundreds, no, thousands of worlds? Isn’t the goal to progress ever onwards and upwards? Isn’t the lesson of nearly every story arc to be less irrational, to focus on logic and reason? In other words, isn’t the story of Star Trek to be more like Data?

Of course, the show would never come out and say that. With every episode, it’s humanity that is emphasized, humanity at the center of attention. It’s a humanist narrative after all. But if you take a step back and realize where the world of Star Trek is heading, the goals of the Federation, the constant incorporation of the other—humanity is trending to become something quite alien. Just look at the episodes where Star Trek speculates on its own future—it’s not pretty when you think about it for more than two seconds.

I haven’t watched every single arc in The Next Generation, so do forgive me if there’s a later episode where the Progressive writers figure out the problem of Data wanting to be human. In fact, it’s a very anti-progressive sentiment. Data is rejecting the part of him that is the other, the thing that makes him foreign. The true Progressive story would be Data being fine as he is, and we should be accepting of him and all his differences. And eventually, portraying Data as being superior to humanity.

But so long as Data remains Pinocchio, he is a walking critique of the Federation, a delicious irony of the very principles the Federation stands for. He is the reactionary beat at the heart of so many stories because his desire to become human implies a hierarchy, that he is lesser for being only Data (no pun intended).

And there’s also a tragedy. Data is working for the very forces which seek to strip humans of their humanity, the very thing he wants to become. Should the Federation ever come to the point of no return, where humanity itself is abolished, then Data will have had a hand in destroying his life goal. And I suppose there is another reactionary story in there as well.

After all, Data is an android. What better way to undermine humanity than to pose to want to be human, only to be secretly serving the forces that will eventually destroy us? I don’t like that interpretation because he’s so loveable, but it’s fun food for thought. Either way, Data is one of those fun questions that always warrants further discussion.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Trantor Publishing to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.