Now that the first book of The Last Human series has been written and published on Royal Road and Season 2 is wrapping up on YouTube, I wanted to do an exclusive retrospective on the journey it took to get here for my generous patrons. This post is not a comprehensive overview of my book, but rather reflections on the nature of writing and my approach towards the craft.

Every one of my stories is a process of gradual realizations, and I want to share some of them below. Given that so much of our space is art criticism and not the visceral experience of art creation, I hope it will provide insight for fellow artists and a peek behind the scenes for readers.

As with all my books, The Last Human started with a kernel of inspiration. I didn’t have a meticulous outline beforehand nor did I have an inkling of the lore or worldbuilding. As I’ve become somewhat infamous for online, I rather dislike worldbuilding and design documents. I find them largely unnecessary for projects with a single vision behind them. Some people find creating their settings their favorite part of storytelling—and no shade on them. It’s up to the individual artist to discover what works best for their process. But I’ve always found the most compelling parts of stories to be the characters. I’m a person who believes the world exists to draw out the colors of the characters rather than the other way around. This does not mean I think worldbuilding should be inconsistent—heavens no.

But what I like to do is introduce a free setting with a very limited POV perspective. I don’t need a thousand year design document to struggle under. I need to understand the small time and place the characters exist in. And then slowly, layer by layer, build everything up around that. And so long as I don’t shatter my own rules, I can keep expanding those horizons as much as I want to. I don’t see design documents as helpful except as the foreknowledge to color the particular scene you are writing. In nearly every other case, they are shackles of pre-conceived notions that restrict just as often as they guide.

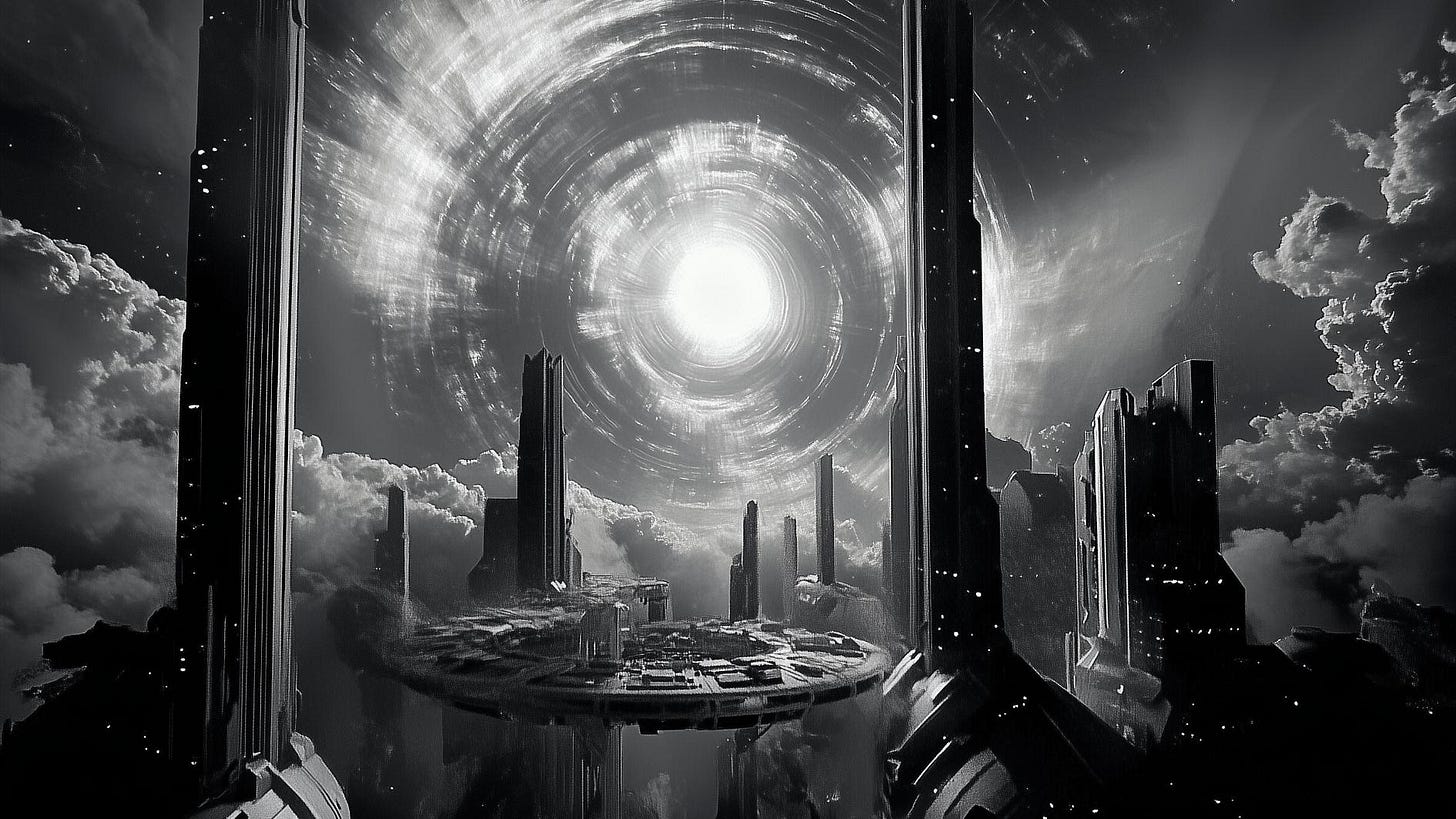

This is all to say that The Last Human didn’t start with a grand sweeping vision, even though I eventually developed one. It had rather humble beginnings. Just as The Domes of Calrathia began with an image of an Astronomer on a pilgrimage to a holy shrine, The Last Human began with a picture of a hooded, lonely human wandering an alien city.

This image was inspired watching the anime called Frieren—which may come as amusement to some of you. For those unaware, Frieren is a fantasy story with an elf as the main protagonist. This small twist on the genre conventions is explored in interesting ways, but I was struck particularly with the long distance of time and how the main character is left utterly alone by the passing of the age. Now this tragedy isn’t something explored greatly in the anime, but it’s an undercurrent that resonated with me.

This great melancholy became the beating heart of The Last Human. My additions to the equation were changing the setting to Sci-Fi and having humanity play the stereotypical role of elves. This trope is normally seen in Sci-Fi as progenitor races or precursor species. Once great, now extinct, this copy and paste cliché usually serves as the excuse for technology magic in the setting and the various MacGuffins to drive the plot. We’ve all seen them. One of my favorites is the Necrons from Warhammer 40k, but they are in practically every Sci-Fi setting out there.

Speaking of, it astounds me how few of these stories have humanity serve as the mythical great race of old. Seems an obvious and shiny hook. But if I had to speculate, seeing how most progenitor aliens are utilized, they’re mostly an excuse for materialist authors to play with transcendental themes. It’s a cheat for Sci-Fi authors to play with magic and God without contradicting their secularism.

But in doing so, I think they lose an opportunity for something. Sci-Fi usually has humanity play the role of the scrappy underdogs new to a bigger universe. It’s a classic opening, and fits very neatly into Progressive ideas in science fiction. Meanwhile the narrative of the downfall of the ancients is usually never our story.

But what if humanity had fallen from grace? What if the survivors had to live in a decidedly post-human reality? What if we lost everything in our sci-fi future?

That’s a story I find compelling.

Ch. 1-5

There’s a common phrase of advice in speculative fiction for those struggling to set a story. Put simply, “What is the most interesting period of history in your world?” Of course, I find this altogether vague and not very compelling. What is “interesting” is entirely dependent on the tastes of the artists. And the things that are “interesting” likewise prove elusive in their definitions. The question authors ought to be asking is not, “What is the most interesting?” but rather “What is the story you need to tell?”

Art is a series of opportunity costs. Just as chiseling marble resolves into a single statue, you are trading everything that blank page could be for a single manuscript. And simultaneously, out of all the characters in your story, you must choose a handful of protagonists at most.

And for my story, only one.

So let’s talk about my choice of hero, for which a similar question must be asked. Why Vas Du’Kaal? He’s hardly what you can call a typical protagonist. He’s a helpless child barely able to speak. His ability to affect the plot is minimal. He’s an incredibly passive main character. And had you taken any writing course in the past twenty years, these traits are exactly what you are warned against. By all rights, he was a poor decision, and I must’ve regretted writing him every step of the way.

It’s almost as if everything they taught you in English class was meaningless bullshit.

The first lesson of art is contrast. Had I ever become an English teacher, this is the thing I would hammer into my students. Writing is no different than the physical forms of art. Conflict is contrast. Character is contrast. Every physical detail and color is a contrast. Every commentary that has ever been written is a dialectic of contrast. This is the mistake of the modern author, wishing to plunge everything into shades of grey. The true writer realizes black and white are the wellsprings of eternal discussion, and I don’t mean black and white merely in the moral sense.

The principle behind Vas Du’Kaal is that he’s two separate characters. There is the child and then there is the old man writing his memories as a child. Yes, my hero is practically a mute. And equally, he’s the most fearsome warlord the galaxy has ever seen. I’ve set two perspectives on both ends of a long gap of history. Why did I do this? Because characters exist in contrast to other characters, the setting, and the morals of the story. By expanding contrast, you expand the potential depth and commentary of the story. I made my protagonist able to viscerally experience events as a child and an old man at the same time, being able to trade between these points of view at the whim of a paragraph. I desired freedom in my setting, and then I also created a character to have the most freedom in said setting.

I always knew The Last Human was going to be a long narrative, and my first strategy preparing for this project was opening the horizons to be as wide as possible. In a single character, I have access to multiple POVs, multiple points of time, and most importantly, multiple points of contrast to detail my story.

Ch. 6-10

Low-stakes conflict is the bane of the modern author. Every crisis has to be for the whole planet and the human race. If the hero doesn’t pull through, the world gets destroyed and billions die. I agree that every story needs a world to hang in the balance to be interesting, but the fact that so many authors can only visualize this in the most superficial and shallow way is an indictment on the modern imagination. Yes, you can put billions on the line and the destruction of everything everywhere all at once, but that’s not a world any artist is capable of fleshing out. It’s an abstraction. What’s the famous quote by Stalin? The death one is a tragedy and the death of millions is a statistic? Well, artists ought to be dealing in tragedies and not statistics. Such is the problem of every superhero movie, and why they are all just the same superficial narrative told over and over.

The world you ought to be putting at stake ought to be as real as that one person. It needs to be so alive that it jumps out of the page. And then you gamble it all on a shaky hand and pair of dice.

Chapters 6-10 is Vas’ first character arc. It’s not about him as a galaxy conquering warlord. It’s about a boy processing the (apparent) death of his adoptive mother. His direct actions have next to no consequence on the implications of the story. In fact, he totally misreads the situation—as children often do—and he thinks things are far worse than they actually are. He believe he’s about to die too and acts accordingly.

That last bit is important. There is a world at stake here. It’s the one inside the boy raised by insects, whether he’s more like the Mantza or more like a human. You’ve gotten glimpses of it before, but here is where the core of his nature is revealed.

Vas believes he got his mother killed, and for this, he decides to accept penance for it. This penance is entirely imaginary on his part, but the important thing is that he does. Such a thought is utterly beyond his former insect masters, let alone the choice to try to make things right. He is a human, and by the redemptive virtue Vas displays, the world is indeed saved. Because while Ingrish coming back is not a result of his actions, their ultimate reconciliation in Ch. 10 is. The Mantza part of him, the part that’s spiritually numb, passes away, and he enters a new way of existing that was beyond him before.

There is another reason underpinning 6-10. The final chapter in this section is called Sojourn, in which our hero remarks upon the melancholy of never belonging anywhere. But there’s a double-meaning. The curse of humanity in this setting is that they are far longer lived than any other alien species, aging for a thousand years before they die. Meanwhile, Vas’ adoptive mother only has a lifespan of fifty years—and she’s already in her mid-twenties. Just as humans physically can’t stay in any one place, so too are all relationships just a passing thing.

How I like to do stories is to present an idea to a reader and then slowly iterate upon it throughout the narrative, examining it from different angles and perspectives. This idea of loneliness is the thesis of The Last Human, and the foundation for all the other concepts.

Ch. 11-15

The next ten chapters are the introduction of a meta narrative. One of the themes of The Last Human is the exploration of language, and the main character’s gradual progression of speech alongside this. If the first ten chapters are about the introduction of words, the fundamentals, these ten chapters are about complexity—drama and storytelling.

Besides the main conflict, there is a secondary commentary on the nature of narratives and art. So, this is an essay explaining storytelling about a story that’s about storytelling.

I like to do a little trolling every now and then.

But what I wanted to explore in this section was the modern tendency to desire to exist inside artificial meaning. Or to put it more aptly, the desire to exist within art.

You can see this with Millennials particularly, people who have walls of Funko-Pop collections and comic book characters. For these sorts of people, art is something to be consumed, not because it makes their lives richer, but because they wish to escape into art.

For them, the essence of a work is meaningless so long as it can entertain them. And as long as they are entertained, nothing else really matters. In the modern man, art has become a substitute for religion, and they are swallowed by these false realities instead of being enriched by them.

Now the Rhodeshi people in these chapters are not a metaphor for Millennials or anything like that, but they are a version of this nihilist philosophy taken to the extreme. Chapter 13 is the main opening of their argument, and the next 7 chapters are the refutation.

The critical thing this philosophy misses, the flaw in modern man’s thinking, is that art should not exist purely to fulfill the vulgar desires of the audience. And when it does that, it becomes nothing more than porn—and it loses the magic that made it so compelling to begin with. This is the magic Hollywood has slowly lost, and even the best modern artists seem to only think in the lowest functions of art.

Art, if it is to exist as subcreation and not masturbation, must have its eye pointed higher. To make it seem real, you must put the work in and expect the audience to put the work in as well. Not everything should exist because it’s easy or fan-service or book-slop. I’m not saying there’s not a place for that kind of entertainment, but the modern art problem is that everything is book-slop. If we’re to have a conversation on higher forms of art, then we need to start with the understanding that it is not easy. It requires hard investment from both the artist and the audience. It’s not all meant to simply entertain and turn your brain off.

The Left makes this argument to justify something like The Last Jedi because they want to excuse their pretentiousness. But they are fundamentally correct that artists are meant for more than jangling keys in front of passive audiences with fried attention-spans.

True art, the best art, is where the story feels so alive that it never needed a storyteller. It’s not a product to be consumed. It has to be more noble than that, and if the Right is incapable of telling stories that are more than that, then we’re going to be stuck in this culture drought for a long time.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Trantor Publishing to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.