Part Four: Founding Myths and the Bumpy Road to Utopia

There are a lot of ways to start at the beginning with Star Trek, so much so that it becomes difficult to choose. Should we begin with the first episode of the original series? Well, which one? Because there’s actually two. There’s the pilot with Captain Pike titled The Cage. It poses some thematic questions with illusion and reality, but it’s not what I would call especially interesting concerning the rest of the franchise. Then there’s the second pilot with Captain Kirk, the man who would actually go on to be a mainstay for the series. Where No Man Has Gone Before has some good moments too, especially in analyzing the Left’s critique of God. But I would honestly go with Encounter at Farpoint from The Next Generation as the best pilot for understanding what Star Trek is. We’ll certainly get to that episode later, but even this I find uncompelling.

I want to start at the beginning—what Star Trek says is the beginning. I want to understand where the Federation came from and why it is what it is. I want to hear the origin story that Star Trek tells itself, and I want to know the justification for how we got from our normal world to the one Star Trek presents.

To put it simply, I want Star Trek’s Founding Myth.

What is a Founding Myth? In real life, they’re essentially our origin stories. They’re supposed to be an expression of our values, explain where we came from, and how we look at the world. They define good and evil, what we hold sacred and taboo. More importantly, they justify ourselves to the world, allowing us to step forward and know whether what we’re doing is right or wrong. Founding myths shape us as a people, as a culture. It keeps our society internally consistent and organized for a collective goal. In short, Founding Myths are our “why” as a civilization, and this applies to fiction as well.

From a meta standpoint, the Founding Myth would usually be a show’s pilot episode. It sets up the context—the principles of right and wrong. It creates the conflict, the thrust of the story, and it asks the “why” which will be answered in the conclusion. But because stories reflect our real world, you also often have internal Founding Myths, in-universe explanations for why things are the way they are. Star Trek’s Founding Myth, the basis of the Federation, is first contact with aliens. And this ironically takes me to thirty years after the franchise originally aired, to The Next Generation movie: Star Trek: First Contact.

To give a short synopsis, Star Trek: First Contact is a time travel movie. Evil cyborgs known as the Borg go back in time to stop the Federation from ever existing. To do this, they’re going to prevent first contact, which is mankind’s discovery of aliens (the Vulcans). Plot happens and the majority of the movie is spent on action rather than philosophizing the actual implications of its premise—which is fine. It’s an enjoyable movie. But to dig into it, you need to get at the assumptions off screen rather than the explicit events happening.

First contact is an idea that you’ll find across the length and breadth of Sci-Fi. It’s treated often as a pseudo-religious awakening, necessary for mankind to realize our true potential. In fact, I would argue it is religious. It’s the atheist equivalent of the eschaton, the end of mankind’s ignorance and introduction into the stars.

Personally, I have always been frustrated that the opposite, the revelation of being totally alone, is never similarly explored. I know the reason why. There’s not much you can do with that idea beyond its shock value, especially if you embrace materialist presuppositions. And more importantly, if you remove the alien, how else are you going to lecture humanity about your political opinions?

The funny thing is, Star Trek: First Contact is not actually about first contact. Very few movies concerning this trope are actually about encountering foreign life insofar as analyzing what alien actually means. If you want a good fiction book that takes the subject seriously, I happily recommend Sphere by Michael Crichton. It’s the best treatment I’ve read thus far, and it’s ironically debatable whether or not aliens even appear in that story.

But most media on first contact is not interested in exploring the possibility of alien life. It’s about putting forward political/ideological ideas and using the alien as a vehicle for those concepts. You’ll find a disturbing trend that the aliens in these movies suspiciously have the same opinions as your average Leftist with just a dash of transhumanism. And I would say this isn’t too sinister on the face of it. It’s extremely difficult to grasp at what an other could look like. We have no real reference point for what the alien might be except what we can find on Earth. This is why whenever we conceive of the alien, it’s always merely a reflection of humanity at the end of the day. And if you hold certain political opinions you view as superior, well, it’s natural what happens next.

But to use the alien as a vehicle for your politics is such a short-sighted use of the concept. It betrays a lack of imagination, and in Star Trek’s case, it also betrays a lack of wisdom.

There’s so much about first contact that makes it the ideal Leftist Founding Myth. It immediately undermines traditional thinking of mankind’s primacy in the creation, invalidating common Western piety. It allows the Left to attack any culture or belief that asserts itself as “correct” and not merely some cosmic accident. It lets the Left appeal to the closest thing they have for a God-replacement—one whose opinions will never veer too dangerously from their own. And they can use it to reinforce whatever activism they happen to be doing that day. The Day the Earth Stood Still literally went from being an anti-war film to getting rebooted into preaching environmentalism. They kept the alien, swapped out the message, and nothing changed. It’s the easiest thing in the world to have a fake alien regurgitating your beliefs while lording its superiority over mankind. First contact is so perfect for the Left it became the real-life wet dream of many atheists. They just assumed fact would follow their fiction.

The only problem? It certainly won’t.

Star Trek’s (and the Left’s) conceit is that they believe the fundamental problem with mankind is a lack of their own example. Religion just needs to be deboonked with facts and logic, men need to learn their privilege, and we need to teach queer studies to kindergartners or else they’ll grow up sexual deviants. They think that if mankind were only shown “their way”, in essence, just another social and moral lens, we would immediately better ourselves. However, if I were to sit down and teach all the children in the world about aliens, I doubt many people would think mankind would be any better off.

Or maybe they would. The Left believe human nature is entirely malleable, that if they did have access to all the children of the world, they could, with the right indoctrination, solve the problem of moral evil. And let’s be honest, exterminate a few choice demographics to boot.

The fascinating thing is the continual moving of the goalposts on the part of the Left. When you look at Star Trek as a religious text—and I truly do believe it’s a religious text—it’s interesting that it leans on this pseudo-religious epiphany that seems to do all the heavy lifting. You would think the Left’s vision would have man achieve the utopia on our own, with liberalism and worldwide democracy and all that. But to do so would mean they would have to outline the specific political and religious answers such a vision would require. They would actually have to solve the question of how to get to utopia. Instead, the story excuses itself with some plausible deniability, after all, we don’t really know what would happen if we were to meet aliens. And that’s how they keep the suspension of disbelief intact.

And meanwhile, it seems so easy from the movie’s perspective. The titular character who brings about first contact, Zefram Cochrane, is a deeply flawed man. He’s a drunk, he sleazily hits on women, and he doesn’t even believe in his own dream. He wants to create the first warp drive for money and an easy retirement. He’s a debased person following his self-interest, the twist being that his greed magically turns into virtue at the end of the story. If I were to ask Star Trek how a world of Zefram Cochrans turns into the Federation, all it could point to is this magical realization of our collective sinfulness. It’s like a switch going off in everyone’s heads, flipping them from bad to good the moment they realize someone out in the cosmos might be judging them.

I see this as the Left coping with the fact, on some unconscious level, that Man can’t do it on his own. He needs a religious revelation to bring about the utopia. It’s not enough to engineer the correct political order. They need their philosophy to spring from the foundations of the cosmos itself. They need to have the alien—their higher power—imposing on mankind. And that is how the Left see themselves—as the aliens in the story. They believe they’re fundamentally distinct from humanity, able to swap sexes and even species at a whim. They believe themselves wholly detached from mankind. Alone, they are the ones capable of emphasizing with the bugs and demons because those things too are separate from humanity. And because that’s not true, they simply wish it into existence with their fiction.

I think the Left are the only group in history that have ever staked their Founding Myth on a completely hypothetical future event. Sure, they have the Post-WW2 consensus, but that’s not the Founding Myth they want. They want aliens coming down in their spaceships and owning the chuds. They want to be the aliens. The Left believe utopia is always somewhere out there, in the murky mists of the future. How do we get there? Who knows. But if only we follow their prescribed politics, the vague plan, we’ll get there one day. And if we’re lucky, maybe the Left will allow us ignorant savages to grovel at their feet for being so wrong.

In reality, humanity would not change one bit if we encountered aliens. Your realistic depictions of the future fall more into the likes of Starship Troopers and Warhammer 40k. And for proof, you only need to look at our real-world equivalent of first contact—discovering the Americas. That’s as close as we’re going to get to finding life on another planet. Did it topple Christianity, with the revelation of an entire continent separated from the Church for millennia? Did it cause men to rethink their violent ways and embrace pacifism? Did this earth-shattering realization do one thing to change human nature?

No.

And with that, I could close out this section here, but I’m going to linger for the sake of a thought experiment. Because I don’t think first contact works well even within Star Trek’s established universe. So let’s rewind a bit, returning to the movie with a few changed details.

Star Trek: First Contact begins again. The Borg are desperate to stop the Federation, a collective that is growing in strength to rival their own. In this end, they send a Borg Cube to Earth as part of a plan to go back in time and change first contact. In their infinite collective knowledge, they foresaw the Enterprise would follow them through the temporal vortex. And so the hive mind hatches a backup plan, a contingency in case their main scheme goes afoul. The crew of the Enterprise do as they do, defeating the Borg and saving the day in the nick of time. Relieved, they go down to the surface to experience the historical moment of first contact.

But the alien ship lowering in the night sky looks strangely different. Riker and Troi share a confused glance. This isn’t the Vulcan vessel they saw from the museums and holo-tapes. The strange spaceship sets down, no less majestically, however. The whole human crowd falls into a hush at this awe-inspiring scene. We now have proof that we are not alone in the cosmos! What will we learn!? What words will be exchanged? How will this change mankind’s perception of the universe? The silence is almost like the beginning of a religious mass, an encounter with God. The only noise is the hissing of steam and the faint whirring of a craft from another world. Suddenly, a gangway lowers and a hatch opens. Three figures appear silhouetted in a bright light. The crowd gasps as the aliens step forward, and Picard can only look in abject horror as this man steps out to greet mankind into the stars.

The Borg decided the best way to defeat the Federation was not some clumsy military assault, but instead a tactical misdirection, making sure it was the Ferengi who first made it to Earth instead of the Vulcans. And suddenly, instead of this quasi-spiritual revelation, the whole thing becomes a farce. Quark starts trying to scam mankind out of our gold-pressed latinum, and when he discovers how backwards we are, he offers a third-rate replicator and a holodeck suite in exchange for Cochrane signing away the rights of the planet. A trade Cochrane happily agrees with.

Have you ever noticed that if first contact was made with any other species in Star Trek, the whole thing falls apart in shambles? I would go so far as to say that if you change the slightest detail in the movie, the premise collapses in a heap. After all, can you imagine if mankind made first contact with the Klingons or the Romulans?

Now from a meta perspective, you might say this is because all the other races in Star Trek are just exaggerations of the Left’s political rivals, and you would be right on the money. I can already hear the criticism that Star Trek was never meant to be analyzed in this way, that to look for any sort of internal consistency in an episodic, poorly stitched together shared universe is to miss the point entirely. The setting, the characters, the plot, it’s all just a vehicle for the moral. You can’t take any of it seriously as it’s supposed to exist in setting.

I agree I’m being entirely pedantic here, but there’s a certain irony in that the Federation does not spring from the universe these writers have created for themselves. It’s the hand of the author that has to constantly intervene, often miraculously and often at the last second, to keep the utopia on track. Mankind’s first encounter was with the one species in the entire galaxy whose values reflected the Federation and the Left. Pretty much anyone else and it would’ve been a thoroughly Rightwing future. Even getting scammed by the Ferengi leads humanity down some seriously anti-Leftwing ideas about mutual cooperation and understanding.

If there’s one thing I take away from Star Trek’s mythological inception—the story it tells about itself—it’s that the dream of the Federation rings surprisingly hollow when you start asking how it is mankind has freed itself from sin. And it’s an amusing coincidence that the rest of Star Trek’s own universe doesn’t seem so convinced either.

Part Five: Unfair Trials and Dishonest Answers

If you ever want to find out what an author really believes, or rather, what his fiction believes, there’s an easy literary tool that cuts right to the heart of matter. I’m sure it has a formalized name, probably in the pages of some dry college textbook about literary criticism. But since I want to take credit for it, I’ll give my own name for this rule of thumb. In nearly every story ever written, there’s what I like to call a “Redemptive Principle”.

It’s not quite the conflict resolution, but rather the lesson you’re supposed to take away from it. It’s what the author believes is necessary to make the world right again. What is the answer to the evils that assail our characters? What is the solution to the hard questions they ask? What is the thing that brings our plot to a close and redeems the whole affair? In most stories, you’ll find the Redemptive Principle is a growth in the characters’ virtue. The cowardly knight must find the courage to slay the dragon, the vain princess must kiss the humble frog, and so on and so on.

Sometimes the Redemptive Principle is a revelation of new knowledge, some new insight. You’ll find this with a lot of detective fiction and its subgenres. In this case, what is necessary to make the world right again—to solve the murder—is a feat of intellect, a deepening of understanding about the world and the fallen nature of man. What is the story of Sherlock Holmes if he is unable to solve the mystery?

In other stories, we also have the inclusion of God (or the writer through Deus ex Machina) as the Redemptive Principle. There are many tales whose endings explicitly rely on a contrivance of fate or an odd coincidence that pushes the resolution onto the side of good. Despite the many great virtues and clever victories in LoTR, it is ultimately the subtle hand of Eru Ilúvatar who ensures the One Ring falls into the lava of Mount Doom.

To be clear, there is no singular Redemptive Principle in most stories. Usually it’s a combination of the three working in tandem, and I would argue those are generally the best stories. But understanding what pushes a story into “good” and what pushes a story into “evil” is a concise way of parsing through narrative beats to get at its underpinning structure. There is also what I’ll call a “Perdition Principle” which is the element of the story that justifies the tragedy and the ultimate fall to evil.

In these two opposing forces, the commentary of the story is laid bare, especially what the author considers “good” and “evil”. All this might seem fairly mundane and obvious, but in expressly laying these things out, I find it useful in stripping a narrative to its most fundamental components. In a surprising number of fiction works, there is a divide between what the author says the Redemptive Principle is and what the actual Redemptive Principle is.

In the case of Star Trek, what is the thing that time and again saves the crew of the Enterprise? What are the elements that rescue them from disaster? And ultimately, what does Star Trek stand for?

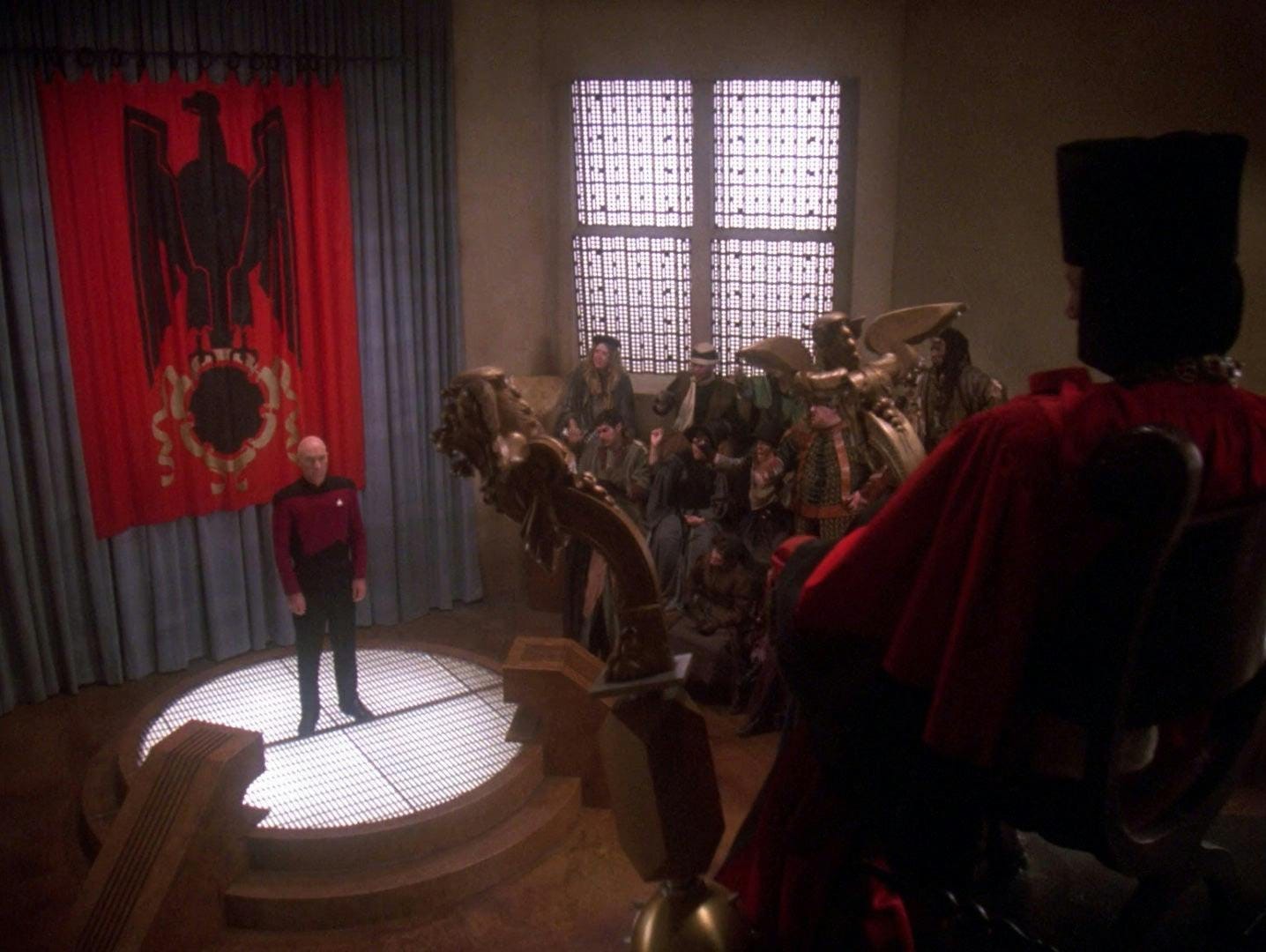

I adore The Next Generation’s pilot episode Encounter at Farpoint as a succinct explanation of what Star Trek wants to believe in. Humanity is exploring an unknown region of space when a mysterious entity called Q shows up and prevents their passage. Accusing humanity of being unprepared and ignorant savages, Q thrusts the crew of the Enterprise in a trial of humanity’s soul. They must solve the mystery of Farpoint station and find a humane solution to the problem before time runs out.

And because it’s the crew of the Enterprise, they do. They figure out that Farpoint Station is actually an imprisoned lifeform and free it. It’s the quintessential Star Trek story, where humanity solves issues through thought and rational thinking, understanding all sides of the problem before finding a moral solution. We are sophisticated enough to rise above violence and savagery, and it is through our intellect that men better themselves.

A cursory examination of Star Trek reveals that much of it is essentially detective fiction. Many answers have the solutions rooted in technical understanding and/or deeper knowledge, the twist being that it is set in space. This allows the writers greater freedom since they don’t have to operate in the constraints of our real world. They control the variables, the rules, and the solution. The only caveat is that they constantly have to allude to this set of invisible constraints (that the characters know of but we don’t) in order to preserve the suspension of disbelief.

How many episodes end with a technical solution like: “We must reroute power from the deflector dish to the phasic field which will dampen the antimatter buildup!” and then another character follows up with “Oh yes, just like draining water from a dam!”

The final metaphor is the narrative coup d'état, Star Trek’s brilliant sleight of hand. It makes the audience believe that the solution was obvious in hindsight, and they could’ve reasonably come to said conclusion on their own, even though with all the pieces of the puzzle, no set of logical loop-de-loops would’ve led them to the solution beforehand.

I would argue these are the truest Star Trek episodes, these are the ones that embody what Star Trek is all about, even the nonsensical techno jargon that comes at the end. Star Trek treats cleverness as the pinnacle of all virtues, raw intellect over strength. It wants itself to be so impossibly advanced, so far ahead, that we can’t possibly question it because it’s beyond our comprehension to do so. It wants you to think that it is through intellect that all other virtues are cultivated, and if only we can put aside all the things Star Trek doesn’t like about humanity, then we can have utopia.

And here we get to another conceit of Star Trek. The franchise sees intellect not as a Redemptive Principle for a particular problem; it sees intellect as a Salvific Principle for all mankind. It sees our IQ as solving all problems everywhere, establishing a world without sin (or at least progressing to one). Our intellects are the justification of our past evils, all a temporary embarrassment on our climb to ascend into a higher state of existence.

Christians get a lot of derision for the Problem of Evil. How could an Omnibenevolent God allow a fallen world? But at least the Christians don’t then turn around and say “the whole meaning of the world, the basis of history, the culmination of our species, the justification for every evil and atrocity and torture, is a future society with a few standard deviations higher on the IQ bell curve”.

When you breakdown all the waxing poetics and banter, this is the argument of Encounter at Farpoint put in its most simplest terms:

Q: “By nature, all humans are ignorant, savage, and evil.”

Picard: “No, we’re not! We’ve changed! We’re smarter now!”

And that’s the game. An unfair accusation followed up by an absurdly dishonest answer. The accusation is unfair not because it charges humanity with being fallen, but that it’s a critique from nowhere. We the audience know Q is judging humanity through an atheistic/humanist lens, but that’s because we know what Star Trek wants us to think. But really, what’s the substance behind Q calling humanity savage? Let’s dig into this. What is the morality with which we’re going to judge the whole human race? Is it ever laid out in clear terms beyond witty retorts and flights of poetic fancy?

I find it fascinating that Picard, upon meeting a god-like entity, only antagonizes it and does everything to dodge the question of guilt instead of asking for Q’s standards. They’re strangely on the same level with all the exact same assumptions about what morality should look like.

Shouldn’t Picard’s first question have been to ask for some version of the Ten Commandments? We’ve introduced a god-entity that is judging humanity, and our heroic Captain doesn’t even ask for the directions? You had the Sci-Fi version of Moses going up on the mountain, and you’re not even interested in what the omnipotent voice speaking back is? And furthermore, who is this god-entity to judge mankind? We assume Q is an authority figure of a roundabout sort, but Star Trek would take a very dark turn if Q had been a malicious trickster devil instead of the helping hand he turned out to be.

But for all the flimsiness behind the accusation, the answer is worse. Picard might as well have said, “but we are not humans! We are Xurg people who also happen to be from the planet Earth!” His argument only makes sense if humanity has transformed in nature, completely and irrevocably, that there are no further circumstances in which humanity might resort to the baser instincts he claims to despise. He’s saying that if the Federation had been stripped of all its technology, that if mankind were reduced back to cavemen, they would still be a completely different creature than their very recent ancestors in the 21st century.

Picard is effectively saying humanity is no longer humanity. That the people of the 24th century might as well be a different species, which becomes a thematic headache if you think about it for more than two minutes. How is it that a show that prides itself on the commentary of the human condition also states in its very first episode that our humanity is effectively extinct, that what we’re witnessing is a bizarre post-humanity that coincidentally happens to wear our faces?

And it’s so strange that in a world of viruses that reverse evolution and god-entities which can turn you into primordial slime, that Picard’s idea of progression clearly has no room for regression.

But the most glaring flaw I think, the ignored and yet painfully obvious contradiction at the heart of it all, is that Star Trek barely comments on the whole point of the trial to begin with. The charge was over violence, accusing the crew of the Enterprise that they did not know how to use violence correctly. That’s the substance of the episode, whether they could virtuously withhold themselves in an opaque situation, knowing when to decisively intervene for the best possible outcome.

Had this been set in Medieval Europe, this episode would’ve been about God testing a knight on knowing when to use a sword and when to keep it sheathed. It’s the exact same basic structure, but instead of God we have Q and instead of swords we have laser beams. However, Encounter at Farpoint barely brings up its most obvious (and most interesting) question on when violence is justified. The episode always vaguely skirts around, with the violence of the past treated as uniformly evil and the violence of the Enterprise always presented in the best possible light.

This distinction of justified and unjustified violence is strangely lost throughout this whole episode. The characters engage in force of arms, and we assume it to be righteous because in the context of the story it is. But we’re never presented with any clear rules. Picard doesn’t argue or ask the question whether any of the violence of the past was justified. He’s handed a list of charges that we never see, and then denies it even applies to him.

He and everybody else assumes that all of it was evil a priori. There is not one time in the episode where violence in the past is brought up as necessary or right. And yet, in the pilot and in future episodes, whenever the crew of the Enterprise engages in violence, it’s all justified. It’s acceptable and noble whenever the Enterprise does it because they (obviously) do it for the right reasons.

To circle way back to the question of what Star Trek stands for, it’s unfortunately a bit complicated and contradictory.

Here we finally get to the RW undercurrent of Star Trek. We get at the contradiction of an egalitarian society producing aristocrats, an environmentalist culture founded on great works of industry, a hierarchical ethic in a civilization that proclaims personal freedom, a people who are always embracing new ideas yet never change, a race of explorers who want the whole galaxy to look the same, and I think it’s most glaring absurdity: pacifistic men who are masters of war.

Star Trek is a story about men who scorn violence and then regularly turn to deploy the most destructive weapons ever devised by mankind.

Now this is not saying the characters of Star Trek are evil for doing so, but it gets at the most fundamental and glaring inconsistency in the franchise. We’re supposed to view the violence of the past as backward, primitive. But it’s also totally justified when we do it. Because when we do it, it’s for the right reasons, and it’s to stop the bad people. Violence is okay when we do it because we’re the only ones in history who are smart enough to wield it properly for a good end.

I wonder if anyone brought up in Q’s trial would’ve liked to voice those exact same reasons.

Star Trek likes to think the solution is never violent force until the writers are forced to employ it to solve conflict. And every time they do, it’s a tacit admission to a truth they don’t want to admit. Violence—virtuous violence—is a Redemptive Principle. Sometimes the moral deficiency in characters is their inability to commit violence. Sometimes the only moral answer to a conundrum is to react with force of arms, and to do so without being able to wash your hands of the gravity and the responsibility afterward.

This is what I mean when the Redemptive Principle is sometimes different than what the authors intend it to be. Encounter at Farpoint was self-contained, careful, and most importantly, too short for the writers to badly stumble over themselves. But the values put forward in the pilot are so many times contradicted elsewhere. Even in the episode, it pretends that Picard found the best solution for everybody. But he didn’t, he screwed over the residents of Farpoint, effectively taking away their home, and backed that with the threat of violence from his ship.

Now we may treat Picard as very moral for doing so, but all I have to say it’s suspiciously lucky that the situation didn’t escalate or cost anyone their lives. What if the residents of Farpoint station had refused to leave and relinquish the creature? What if the planet had threatened war with the Federation for interfering with its sovereignty? What if Picard had to get his hands dirty to free the imprisoned creature, with the lives of innocent children killed in the crossfire? How moral and upright would the series have viewed him then?

I’m not saying Picard would necessarily be immoral for conducting such a war, but the series has a strange tendency to condemn such wars and those who start them. It’s very easy to see the situation devolving into the savagery that the series plainly states that it’s so far above. And it’s awfully easy to make great claims of mutual cooperation and greater understanding, of meeting peaceably with the alien and the unknown, when the people you’re lecturing can’t fight back.

If you want a good encapsulation of Star Trek’s view on violence, I recommend this interview with Leonard Nimoy here:

Star Trek wants violence to be clean. It’s nearly always the Federation who comes up with spotless hands. And when it’s the Federation on the backfoot, when it’s the Federation being maliciously attacked, those same claims of the primacy of mutual cooperation and greater understanding go out the window as was when with the Borg. “But the Borg won’t compromise!” I hear some people saying. “They are an existential threat!”

Oh? Are they now? Are they the same kind of existential threat which Star Trek so loves to lambast as alarmist and irrational thinking? Or are they the real kind of existential threat? The kind that is existential to us who are totally unlike all those savages who don’t know any better? Have the Federation really exhausted all other options? Here, why don’t you go beam aboard this Borg cube, let’s have another gander at some peace talks.

To be fair, Star Trek clearly isn’t against all violence. Self-defense is pretty consistently treated as the right thing to do. But it never becomes much more sophisticated from there. It’s schizophrenic in its own assertions, the plot always contriving the Enterprise to avoid the sticky sides of any situation. And that wouldn’t be such an egregious thing if Star Trek didn’t pride itself on being so separate, so uplifted from the rest of mankind.

Even when they kill people, do you notice they almost never get blood on their hands?

And then to blanket condemn the past for its savagery without taking the time to understand it reflects the kind of close-mindedness that Star Trek loves to indulge in. One notices that it’s nearly always violence treated with suspicion, to be used as the last resort. Never is tolerance and diplomacy examined so ruthlessly, put to trial so meticulously. I’ve watched hundreds of episodes of Star Trek, and I struggle to recall a time where the Federation was criticized for being too tolerant, too merciful, too open to peace.

Well, except maybe once…

“Open your eyes, captain. Why is the Federation so obsessed with the Maquis? We've never harmed you. And yet we're constantly arrested and charged with terrorism. Starships chase us through the Badlands and our supporters are harassed and ridiculed. Why? Because we've left the Federation, and that's the one thing you can't accept. Nobody leaves paradise. Everyone should want to be in the Federation. Hell, you even want the Cardassians to join. You're only sending them replicators because one day they can take their 'rightful place' on the Federation Council. You know, in some ways, you're even worse than the Borg. At least they tell you about their plans for assimilation. You're more insidious. You assimilate people and they don't even know it." -Michael Eddington

Right there is the greatest monologue in Star Trek. Consciously or not, it’s the show finally coming to one of its few epiphanies of self-awareness. It’s why the Dissident Right loves DS9 so much. It’s Star Trek being honest with itself and examining its core assumptions and realizing that something is coming up short.

The greatest moments of Star Trek, the ones that give the show a real soul, are always the ones where the show implicitly (or explicitly) puts aside the liberalisms and confronts harsh reality. It’s in those moments when the writers don’t Deus ex Machina the problem away and live with the consequences—at least for a little while. It’s Captain Kirk’s rage and mourning over Spock’s death. It’s Picard’s humbling after being assimilated by the Borg. It’s Sisko who (alone of all the Captains) danced with the devil in the pale moonlight.

These are not the actions of perfect men who stand above human history like nascent gods, waiting to transcend the fallen flesh they hate. These are men who are intimately involved in the drama of human history and wrestling with it in their own way, with the virtues and the sins.

It’s always in those moments of imperfections, those acknowledgements of sin, of ignorance, of being humbled, that Star Trek becomes the most human. There’s a tug of war in the franchise between what writers need for an interesting story and what they need for the politics they espouse. The good episodes are always those that confront the ugliness of the human condition rather than run away from it. And re-watching this franchise, I can’t help but notice it’s always those monologues about humanity’s improvement, the betterment of the species, that fall more and more flat with every passing year.

I can go on, but what made Star Trek great was its silent reliance on Rightwing themes despite its Leftwing politics. It’s always in these implicit moments, the actions behind the demagogues, the heartfelt tragedies in utopia, the military uniform always on screen, that we get at the real Star Trek. Peeking under the surface, you’ll find a surprisingly reactionary future despite what’s coming out of the character’s mouths, and DS9 is hailed as the greatest because the writers forgot they needed to pay lip service to the liberalisms. But once the propaganda finally overtook the substance, then it collapsed as a franchise like all the rest.

Part Six: A Universe of Horrors

Star Trek is one of the most terrifying fictional universes put to screen. People forget that fact because of the cozy atmosphere of the Enterprise, but I’m here to remind you of the grim darkness of the far future. I mentioned a few examples already, viruses that regress evolution, malicious god-entities, rampaging cyborgs, etc. etc. But the truth is, that’s only the beginning of this very deep rabbit-hole.

Why do I consider this topic important? How does this contribute to the Rightwing future I spoke of in the title? We’ll get there. Trust me for a second, and let’s run through a short list of my favorite scenarios first.

Whenever you step into a transporter, you die. Your body is disassembled and reassembled somewhere else, and every single time, a clone of you walks out. But that’s not the horrifying thing. Have you ever wanted to be duplicated? Have you ever wanted another you? Husband to your wife, father to your kids, friend to your friends? Do you ever want to walk into a room and all your loved ones are there, laughing and joking along with someone else who wears your face? But that’s not someone else. That person is you in every possible way you are. And who’s to say they don’t have a right to all the people in your life?

Shall we go to the holodeck episodes? What if you were trapped on the holodeck? How would you ever know the difference between the simulation and real life? I mean, you can touch everything. You can smell and taste and do everything you had in real life. How would you know it’s fake? How would you know there’s nothing behind your coworkers eyes when you talk to them? What if it’s all an illusion? And how would you wake up every morning never knowing for sure? Or worse, what if you’re part of the illusion too? You’ve magically come to consciousness one day, and you’re part of some game created by beings no different than you—except they are real and you are not. And one day, at their convenience you’re switched off. No pain, no warning, in one moment—in a blink of an eye—you’re gone. But think of the horror on their side! They might be part of a larger simulation. After all, if they can recreate you, who’s to say no one can recreate them?

Moving on from our existential horrors, shall I welcome you to the terrible diseases of the far future? We’ve got a little of everything! I’ve got viruses that scramble your speech, make you act out all your inhibitions, and kill you if you’re past puberty. We actually have several viruses related to age for some reason. Have you ever wanted to spend your early twenties and thirties in a few days? Insanity is the least of what you’ll encounter in the frontier! You ever wanted to be turned into a monkey, a spider, or perhaps an alien? Losing everything you ever were, your memories, your mind, and becoming something entirely non-human? Have you ever wanted a virus that bursts out of you like a xenomorph?

Maybe at least our neighbors are nice? Well, that depends. The aliens that just want you dead are a drop in the bucket compared to what else is out there. Heck, I’ve got races that will hunt you for sport! If I had a nickel for how many organ harvesters we encountered, I would have two, but it’s kinda weird that it happened twice. Listen, I’ve got aliens that will replace you, aliens that will wipe your memory, aliens that will make you think you were the alien all along, aliens that will remove your consciousness from your body, aliens that will go to town on your body (and not in the good way), aliens that will clone you, aliens that will seduce you into raising their young, aliens that will make you—yes, you, the man reading this—pregnant!

I spoke of malicious god-entities, and there’s many more than just the Q! Ever wanted to be experimented on? Forget epic trials for mankind’s soul, you’re needed for medical research! Or maybe just for the gods to have fun a little. Immortality gets boring and death is so exciting! And don’t think you’re going to escape the notice of your creators! We have so many of them! We’ve got Greek gods, Bajoran gods, shapeshifting gods and ethereal cloud gods, we have the Christian god (no, but not really, lol), we’ve got more inter-dimensional, pan-temporal, and omnipotent gods than we know what to do with! And not a single one of them are actually decent to worship! Best not get to many ideas of a savior figure. We don’t want religion sneaking into our rationalistic setting!

And for horrors beyond your imagination, I’ve got just as many as those! I’ve got doomsday machines blowing up whole star systems! Worse than that, I’ve got a probe that was going to kill Earth because of the whales! I’ve got an amoeba a mile wide that will suck the life out of you! We’ve got rampaging crystalline entities, salt vampires—and I just want to mention again—aliens that will make men pregnant! Did you know if you go too fast in Star Trek, you’ll be forcibly evolved into a slug creature? (Check that weird one out, it’s from VOY: S2E15). I’ve got the culmination of a species’ sin which was abandoned on a barren planet as a black sludge creature! His name was Armus!

Oh, and after all that, what are your thoughts on being cocooned?

If you couldn’t tell, I had a great deal of fun writing that rant. And that list was just from the top of my head. To play a fun game, I’ll add a shoutout in this essay to the first person who posts all the episode references in the comments.

Anyway, why do I bring all this up? I find horror to be the Reactionary’s genre. It goes against what the Left always want to do—to incorporate the alien, the strange, and the other. Horror draws boundaries; it lays out a definition of evil, and it’s so visceral that the Left can’t argue their way out of the objection. They can try, but it’ll end with them taking the side of the bugs, and then the game is up. Horror is an inversion, and through that inversion, is an expression of objective truth, of objective beauty and aesthetic—things the Left despise.

You can paint over these themes, you can sweep them under the rug, you can even try to forget them come next episode, but if you ever pause and think for five minutes, you start to come to conclusions. Some of these conclusions Star Trek stumbles into, like how you ought to forbid tampering with mankind’s genetic code. But many more are left unsaid, unspoken, because to address them seriously would mean compromising Star Trek’s vision. After all, are we really going to take seriously the existential crisis of meeting a malicious god? Are we really going to talk about the serious implications of duplicating a person? Are we really going to continue gallivanting about in family friendly spaceships while the galaxy is crawling with indescribable monsters? Remember, in The Next Generation, there are the kids on the Enterprise.

To take these issues seriously, to realize you inhabit a Rightwing future, is to destroy the heart of Star Trek. It’s not just about the transporters and the spaceships. What does Star Trek do with the problem of evil? It spends one episode exchanging witty remarks and then quarantines it on a planet.

And I can hear the critique I voiced in the beginning. This is all just Star Trek playing with fun, episodic concepts. These concepts were never meant to be woven into a cohesive picture, and they’ll make your brain burst if you try. I shouldn’t look too deeply into any of it, and to do that is to go against the spirit of the show.

I brought this critique up facetiously earlier, and I’ll seriously address it now.

I think that perspective is flawed for two reasons. First, the whole spirit of Star Trek is to think deeply about the big problems. It’s a franchise dedicated to morality plays and sci-fi ideas and trying to play with the issues of the future. To not take it seriously, to turn my brain off and enjoy slop, goes directly against the ideals all the classic shows present. You might as well posit Star Trek was never trying to say anything, and that entertainment has no purpose beyond what’s presently happening on screen. Second, it’s notable on a metatextual level, that writers across multiple decades constantly played with ideas which should’ve destroyed the show. Most of these ideas, taken to their logical conclusion, should’ve destroyed the Federation and the utopian vision Star Trek was trying to present.

I mean this both figuratively and literally. There’s an episode where parasites infiltrate the highest ranks of the Federation, compromising the heart of Starfleet, and do you know how many times this gets brought up again? Zero.

The show always resets itself. The Captain saves the day, and the problem is shuffled offstage with a Deus ex Machina ending. So very rarely are the hard questions asked—the kind Star Trek prides itself on. What are the spiritual implications of meeting a fallen god? What if we could reshape human nature into whatever we wished? What if, in our incredible scientific advancement, we could dissect the secrets of creating a human soul?

The first layer of Star Trek is a utopian vision of the future, but underneath that, there’s a second layer. This franchise casts a long and surprisingly hellish shadow under its comfortable veneer, a future of indescribable horror occasionally bubbling up to the surface. This bold frontier we’re exploring doesn’t seem so inviting when death or worse seems to lurk behind every corner. And how ought we to face those things?

What should you do with a galaxy that you can’t negotiate with, that seeks to inflict nearly every misery and evil upon mankind imaginable?

What should you do with a galaxy filled with horror? You can rely on your intrepid Captains, singular men with great intellectual capacity. You can outthink, outwit, and outfox for as long as you can. But realistically, sooner or later, one of those Captains is going to fail. A catastrophe is going to strike the Federation, the likes of which it isn’t going to be able to handle. And when this calamity strikes, who are the sorts of men we are going to turn to then?

There’s a third layer to all of this. Think of it as a shadow cast by another shadow. This is where you get to the heart of reactionary Star Trek, where all the fun analysis is. What are the proper responses to the ideas Star Trek presents? Beyond the obvious ideology of our characters, what are alternate solutions? What are the more moral solutions? And from a writer’s perspective, what stories can we derive from these branching possibilities?

I’m not interested in examining Star Trek and making nitpicks like a YouTube critic analyzing The Last Jedi. I’m not writing this essay trying to point and laugh at every contradiction for not making sense. Truthfully, I don’t expect Star Trek to make sense. But I bring these objections up because I think they are very interesting writing prompts, sources of inspiration other authors can use for their own works. And I want to push beyond the shallowness of our present culture to strike at something real again.

Let’s face it. Star Trek is exhausted, and frankly, I’m finding many of its answers unsatisfactory in the present day. It was wrong on a lot of things, not the least of which was on the nature of the human soul.

The thing is, I like Star Trek. There are many parts of it I downright adore. But I would rather have something new now. I want something that’s fresh in a way Star Trek can’t be anymore. I’m tired of Kirk holding back, Picard’s constant arrogant pretensions, and Archer’s spiritual crisis. Even Sisko, the right man in the wrong time—he becomes stale after a while. I want a story that tackles the hard questions in a way Star Trek never could. I want a Rightwing story in a Rightwing future. But before we get to that, I feel as though I’ve been beating a dead horse with how Star Trek doesn’t live up to its reactionary themes.

So next time, let’s talk about what made Star Trek great.

It's hilarious how far the 90s shows go out of their way to show the Federation as a secular liberal utopia, flawless and intellectual, moral to a fault. And meanwhile you can't turn on anything made after 2014 that doesn't cast the Federation as a corrupt, meddling bureaucracy of impotent white men torturing aliens in secret rooms.

If Trek was always the fictionalization of liberal fantasies, it's interesting that the Boomer fantasy was the achievement of a secular liberal science utopia, and the Current Year fantasy is that this utopia was always corrupt, compromised and racist to its core.

Looks like someone might have created a monster...

I always felt the Maquis were right if you watch the show from the outside. But wrong if you are immersed.

I mean, if you buy into the premise that the federation has solved all the major problems (on Earth at least). No poverty, no hunger, no war, etc. Then Eddington and the Maquis are idiots for wanting to leave paradise.

But when you look at it from the outside and know that The Federation's Utopia is left wing fan fiction, the Eddington's critique is no longer aimed at the Federation, but at the writers.

Excellent article!